Category 10

Four Personal Stories From the Aftermath of Hurricanes Irma and Maria

JUNE 2, 2018

SAINT THOMAS, U.S. VIRGIN ISLANDS

I’m not sure if we’re inside or outside. The sun is beating down on Leticia Duncan and me as we stand in her living room, and I suggest that we move our conversation to a more shady area. Ten feet to our right, a surviving portion of the roof shelters an empty, kitchen-shaped space from the direct sunlight, and as we step around puddles of water I notice a cloud of mosquitoes forming at our ankles. Neither the bugs nor my audio recorder seem to bother her as she tells me the story of this home – her family home of many generations.

“This house is a remembrance of my family – of all we went through,” she says. “Everyone was in this house. I can’t let it go, too many memories.”

At first I’m surprised she agreed to meet me here in the middle of the day. Duncan is a Patient Care Technician (PCT) at the only hospital on Saint Thomas, and since she works night shifts, this is usually when she would be asleep. But as we talk, it’s clear that she’s wholly present in this moment, an aura of fierce energy and passion radiating through her words.

“I remember the day of the hurricane. I had just finished my shift, and I was telling my boss I was going home, and she was like, ‘you can’t go nowhere!'” She clarifies that during hurricane warnings, island-wide curfew is in effect, and nobody is allowed to be on the roads. “I really didn’t have much for a change of clothes. I knew my house was strong – or I thought I knew my house was strong. Long story short, hurricane came, destroyed the house.”

As she talks, I quietly survey the damage. Most of her roof has been peeled away, and the ridge beam supporting the remaining section of the roof is rotted through, a product of months of exposure to the elements. The walls are stripped down to the frame; only a skeleton of bare 2×4’s trace the outline of what used to be separate rooms.

“IT WAS A LEARNING EXPERIENCE FOR ME”

After a few days of work, the team of volunteers has nearly finished gutting the inside to remove any traces of mold. The floors have been swept and all of the debris cleared. As Duncan and I talk, the volunteers are outside taking a water break, leaving us in an eerily silent house, interrupted only twice by the sounds of dump-trucks driving nearby. I ask her where she’s been sleeping since the hurricanes.

“Oh, in my car. Or wherever I could,” she says with the slightest chuckle. “It was a learning experience for me. I got to learn how other people live… to see how they are… to see how it is to be homeless. I stay by my sister sometimes… I have days when I can go there and days when I can’t because there’s so many people that there’s no space. I don’t get mad, and I’m not upset. It was an act of nature.”

She applied for FEMA aid and was given some money, but it didn’t even come close to the amount she needed to start the work on her house. She reapplied, but was turned down.

“It was hard for everyone,” she says softly.

(Pictured Below: Volunteers clear debris and moldy drywall from Leticia Duncan’s house, two days before our conversation)

“CATEGORY 10”

On September 6th, 2017, Hurricane Irma raged through the Caribbean, hitting the Virgin Islands as a Category 5. With sustained wind speeds of up to 185mph, it has been declared the most powerful Atlantic Hurricane in recorded history, dwarfing the seasonal storms of recent years and leaving a trail of destruction through islands already prone to food shortages and high poverty rates. Tens of thousands of people were forced out of their homes.

Then on September 19th, just two weeks later and without much warning, they were hit again by yet another Category 5. As some of the locals put it, Hurricane Maria destroyed what Irma didn’t. Intense flooding, black mold, and insurmountable piles of debris became a normal part of life. One hundred per cent of Saint Thomas’ 55,000 residents were affected, and some locals refer to the combined damage of the storms as a “Category 10.”

“JUST KEPT PRAYING THE WHOLE NIGHT”

As horrifying as the situation was, for some, the hurricanes weren’t the only cause of stress. As Irma drew closer, Loritta Pickering was thinking about her baby; she was nine months pregnant, and due at any moment when she was forced to take shelter in her closet, huddled together with her mother, son, and nephew.

“I’ve been through Hugo, and I’ve been through Marilyn, so I thought I was prepared,” she tells me as we sit at Picasso’s Coffee Bar, a local artisan coffee shop that she manages. It’s April, 2018.

“I was calm, I was really calm. You don’t want to be stressful, being pregnant and going through all of that. We went into… all of us went in the closet… and the roof decided to go, so [we moved to the bedroom] and we were able to stay there in shelter throughout the whole storm until the following morning, covered with a mattress and everything. Just kept praying the whole night.”

She hid there with her family for fourteen hours.

“You’re not sure what’s going to happen. You just pray for the best. It was really scary. We didn’t know if the rest of the roof was going to go or if something was going to come in through the house or blow us away.”

“AS BAD AS IT LOOKED ON TV, IT WAS EXACTLY THAT BAD. IT WAS HORRIBLE.”

After the storm passed, the Saint Thomas hospital was badly damaged, so she had to make the journey to the nearby island of Saint Croix to deliver. Thankfully, both she and her baby, as well as the rest of her family, made it through the storms safely.

The same cannot be said about her house. The portion of their roof that had blown away had been scattered across the hillside, leaving the inside and all of their belongings vulnerable to water damage before the Army Corps of Engineers were able to put up a temporary plywood roof and tarp. Their walls, floors and furniture had all become a perfect habitat for black mold. Pickering’s nephew Lionel Blucher tells me about it was we stand outside the house.

“There were five big whooshes, and you could feel the whole house shaking. On the second big whoosh, we heard the wood cracking from the roof, and that’s when the rain started coming down. The water started coming down through the cracks in the roof. That lasted for another three hours. Then around 7:00 PM they’d said the storm was supposed to pass, but [it] didn’t really let up until about 5:30 AM the next morning.”

As we talk, volunteers from All Hands and Hearts – Smart Response are outside with us, cleaning up the debris in the yard and loading it into a nearby dumpster. This is their second day of work on the Pickering’s house, and it won’t be the last; it’s expected to take about two more days to finish gutting the mold from the inside. I ask Blucher about what he thought of the media coverage after the storms.

“As bad as it looked on TV, it was exactly that bad. It was horrible. … In my 27 years, I have never gone through anything like this.”

He was a child during hurricane Marilyn, a Category 5 that devastated the islands in 1995.

“Even speaking with the elders, out of all their years they’ve never witnessed something of this magnitude,” he says heavily. As he talks his gaze stays focused on the volunteers, and I wonder what it must be like to watch complete strangers pick up the pieces of his childhood scattered across the lawn. He points as someone pulls a plastic stencil from the rubble, and tells me that it reminds him of grade school.

“I don’t really have any enemies,” he jokes, “[but] I would not wish this experience on anyone.”

Blucher and I walk up to the house. He’s a professional music producer and DJ going by the stage name of Jeaucar Made the Beat, and usually spends most of his time in Florida; however, due to the hurricanes, he’s decided to stay here on Saint Thomas for a while to help his family recover. I ask him what kind of effect this experience has had on his life and career as a musician.

“I still want to pursue [music]… but at the same time, when you have devastation that hits home, as hard as this, it’s kinda hard to balance both. … I didn’t realize it until I went back to Florida recently, but it took a toll on me mentally as well, because that kind of traumatic experience … it really showed me how important mental health is.”

Inside the house, he shows me around, and points out some of his musical equipment that didn’t survive the storm. A large MIDI keyboard that he says he’s had since he was a kid took some heavy water damage.

All Hands and Hearts has been on the ground in here in Saint Thomas since right after Irma hit. After being evacuated for Maria, they came back on the first flight they could get and immediately started work on people’s homes, clearing debris, gutting drywall, and removing mold. To date, they’ve worked on about 440 homes and a couple of schools, helping thousands of people on their journey to recovery. Without doing the debris removal and mold remediation, homeowners can’t start the rebuilding process. Although some people are able to muck out and gut their own homes, for many, the intense physical nature of the work is too much. For those left to do this work alone, it can be daunting, and difficult to even know where to begin.

“WE MADE A FULL BREAKFAST”

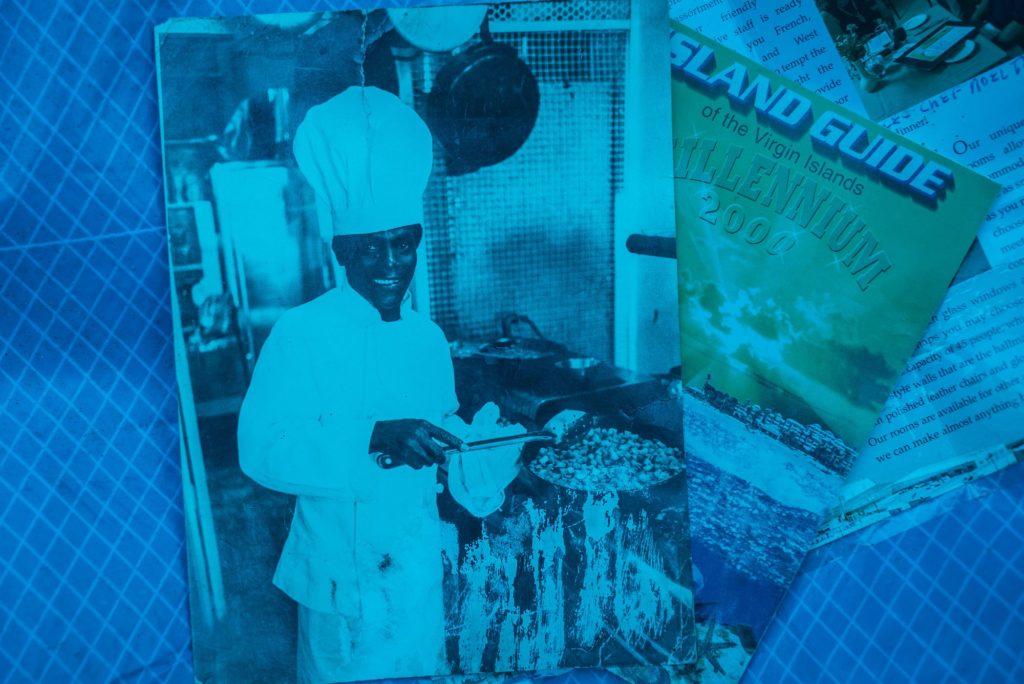

Noel Thomas knew exactly where to begin, and he knew the morning right after Irma.

“I came in the kitchen and it was underwater… and I made breakfast.”

“Wait, you just made breakfast?” I ask in disbelief. My colleague and I look at each other, not sure whether to laugh or not. I can’t seem to wrap my head around the image of Mr. Thomas standing in ankle-deep water, making breakfast as if his roof wasn’t peeled back like a metal can lid.

As if unable to understand my confusion, he replies with a smile, “I took a frying pan and rinsed it out, and I said, ‘I’m going to make breakfast.’ Scrambled eggs, we had some butter bread—no electric, no toast—and we had some bacon. We made a full breakfast. I had my cup of coffee, and some tea [for my wife].” Mr. Thomas was the head chef at a local hotel restaurant for many decades before retiring, so in the wake of such a traumatic experience, cooking breakfast for his wife may have been a healthy coping mechanism.

He leads my colleague and I through his house as he hums a faint little tune, pushing away hanging electrical wires and stepping through puddles in his living room with his high-top rubber boots. In the absence of a roof his home is covered by a thin blue tarp; water has pooled in certain areas creating ominous stalactites that hang down into the rooms. We enter his bedroom, and he begins to dig through some stacks of objects wrapped in garbage bags. After a minute, he finds what he’s looking for—a couple of photos and a large framed painting, a collection of memories from his years as a successful executive chef. He’s grinning ear to ear, even more than usual.

He also shows us his collection of old guitars. He has four or five, and some of them seem to have weathered the storm okay, while others look badly damaged. Thomas is a musician as well, and has recorded a few records throughout the years. He also has an organ that sits against the wall, water-logged and covered in a tarp.

“WE SAW THE CEILING STARTING TO FALL DOWN”

“My wife and I, we were both here… They were reporting about the danger of [Hurricane Irma], and everyone was preparing, and I remember at the time I went on the roof and nailed a couple of boards to keep the galvanized on a little.”

“We shopped for groceries that would keep for a few weeks. Dry goods. We had a generator,” he continues, his warm smile never faltering. “The first thing we experienced was a little… 40mph wind come in, coming slowly. It’s darkening up a little now… Then it was up to, I’d say like, 75mph or 100mph, and we just kept in silence, talking with each other, trying to make each other feel happy. At about, uh, half an hour after that… we saw the ceiling starting to fall down… Then came now, we could hear the galvanized stripping… Then the water started coming in. The water started coming in. It was so powerful. We had to get out of that area real quick. I went to the other room, that was about the same. Water. We said a little prayer, and then when we looked at the house, it was all flooded. The bathroom—that was the only room that was a little dryer. It had a little leak coming down slowly … we stood in that room [the whole night].”

As if he were recounting a favorite memory, his cheery disposition persists through every word, impossibly uplifting and undoubtedly genuine.

“When I came out that morning, these two doors were gone. The steel roof and galvanized, all up… It was terrible. It was really terrible.”

At this point I can’t help myself but to ask how he can be so at peace while recounting such dark memories. How can someone with a leaky tarp for a roof be so positive?

He chuckles and nods.

“It’s hard, you know, it’s very hard,” he says, “but if you worry, you’re going to get sick. And that’s not going to help you. So you’ve got to keep the spirit up! It’ll keep you going, you know? If water comes down, it’s going to come down. Most important is life… Anything else can come after that.”

“I’M STILL HOMELESS”

The Island of Saint Thomas has been through a lot in its short history as a territory of the United States of America. Since 1917, when it was purchased from Denmark as a political pawn in World War I, it has suffered through political turmoil, financial hardship, and multiple catastrophic hurricanes; however, the back-to-back Category 5’s of 2017 won’t be forgotten any time soon. Some disaster response experts, such as Greg Forrester, President of the National VOAD (National Volunteer Organizations Active in Disaster), are predicting a multiple-year recovery assuming 2018 doesn’t bring more storms.

“When we look at the challenges to even bring in relief response and recovery,” says Forrester, “we have to have a means by which to bring in those volunteers that doesn’t impact the delicate infrastructure that’s already [here]. So we have to look at … how do we actually move equipment and people around? How do we feed them? How do we do it in a way that doesn’t inhibit the relief supplies coming in for the inhabitants that are [here]?”

I ask Forrester what the next few years might look like.

“I think we might still be seeing houses under repair ten years out,” he says. “It depends on the amount of financial resources that come in. The difficulty here is because of the widespread disaster in other areas of the United States; we may not be able to draw down the personnel and the volunteers necessary to make it happen in three to five years.”

He’s right, and it’s a somber truth. For both of these storms to have happened at the same time Harvey hit the mainland U.S. is frustrating for the people of the Virgin Islands, who mostly feel forgotten by their fellow Americans. Most of them are used to mainlanders not knowing where their islands are, or that they’re even citizens at all.

“We’re in April,” Leticia Duncan says. “Hurricanes were in September. I’m still homeless. I still go by my sister’s sometimes, I still go by my friends’ sometimes, and they understand. They are not mad, they don’t get upset. But… asking for help and getting help is a challenge. Some people come and help, some don’t.” Her tone becomes more upbeat as she continues, “honestly and truly, All Hands and Hearts is the first. Honest to God, the first that actually came here and made me feel good… I’m not lying. You’re the first who actually said, ‘I can help you.’ Everyone was else was saying, ‘I can’t help you.’ They saw the condition of my house and didn’t lie, didn’t sugar coat. They said straight up, ‘I can not help you.’”

“I’LL BE RIGHT HERE”

As the 2018 hurricane season draws nearer, many Virgin Islanders are left with the difficult choice of staying on the islands or abandoning their homes to take shelter on the mainland. Thousands of people are still without proper roofs, and many of them don’t have the money or documentation to purchase a one-way ticket to the continental U.S.. Even fewer would have a place to sleep once they arrive.

For others, leaving isn’t even up for debate.

“I don’t care if they’re predicting a Category 9! I’ll be right here,” says Eureece Thomas.

She’s one of about 8,000 residents living in Anna’s Retreat, a region of Saint Thomas that was hit especially hard by Irma. Her entire roof was ripped off and all of her belongings were lost, but she shares the same traits as many others in her shoes. Strength, resilience, and camaraderie are deeply rooted into the island’s culture, and the determination to thrive spans many generations.

Although their houses may be gone, Saint Thomas will always be home.

––

Connor Shafran is a photojournalist and videographer based in Los Angeles. From November 2017 through April 2018, he lived on Saint Thomas and worked with All Hands and Hearts to document the island’s recovery.